God’s grace, peace

and mercy be with you. The title of my sermon is Inheritance, Baptism and

Suffering, and my focus is our Epistle (1 Peter 1:3-9). Let us pray. Heavenly

Father, the psalmist wrote, “I rejoiced when they said to me, ‘Let us go

to the house of the Lord.’” Now that our feet are within your gates, we

rejoice to hear your Word. As we listen, may your Spirit enlighten our minds

and move our hearts to love deeply as Jesus loved. This we pray to you, Most

Holy Trinity. Amen.

As I was preparing

this sermon, I thought I could shorten it to three letters, but once having been

inflicted with the illness known as IBS, I thought not. Then, I recalled that

God does have a healthy sense of humor, and discovered that the acronym IBS can

mean many other things, such as International Business Systems, Internet

Banking System, Inductive Bible Study, Institute for Biomedical Sciences, and

1,600 more. That said, with no pun intended, let’s move on to my first point,

Inheritance.

The land which I

own came to me through inheritance. My grandparents, John and Helen Cwynar,

purchased 81.2 acres on Mowry Road in Potter Township from the Rambo Family on

March 22, 1946, which was 11 years before I was born. I inherited 21 acres from

my father. Those of you who have inherited anything know that it comes with a

cost, an inheritance tax, which varies on your relationship to the original

owner.

By definition,

many things can be inherited: property, genetic traits or material possessions

like art or furniture. In addition to our land, I inherited some antiques: some

kerosene lamps, my father’s three finger baseball glove, a few end tables and a

horse-drawn rake. The French gave us the word after borrowing it from the Latin,

inhereditare, which means to put into possession.

Someday, someone else will possess all the stuff I now own.

Peter’s First Letter addresses “the elect strangers of

the Diaspora.” The Diaspora or the dispersion of Israelites beyond the

borders of the Holy Land came about because of war, exile, forced dislocation

or voluntary resettlement due to commerce and trade. As Christians or early

members of the Jesus movement, they lived in a precarious social condition

among an alien, Gentile society. They were disenfranchised, and subject to the

ignorance, slander and hostility of the locals who were suspicious of their

intentions and allegiances. Such was the perennial predicament of strangers in

the ancient xenophobic world.

Peter addressed these early Christians who faced the

perennial problem encountered by all displaced peoples: maintenance of their

distinctive communal identity, social cohesion, and commitment to group values,

traditions, beliefs and norms in the face of constant pressures urging

assimilation and conformity to the dominant values, standards and allegiances

of the broader society.

These elect strangers shared the same paradoxical condition

with their Lord and Savior – vulnerable and lowly, yet elevated to an elect

status. Peter conveys the idea that they share the same status with their Lord

in order to provide them with hope even in the face of suffering. Following

Christ’s example of obedience and submission to God’s will, these people served

as a model for Christians for the next 2,000 years, including us today.

What is it that these early Christians would inherit and how

did they come into its possession? Inherit or inheritance appears over 500

times in the Bible; 455 times in the Old Testament and 49 in the New. In the

Gospels, Jesus is asked to settle an inheritance quarrel between two brothers

(Lk 12:13). He speaks of inheritance in the Beatitudes (Mt 5:5) and the Great

Judgment (Mt 25:34). In several different ways, Jesus is asked about how one is

to inherit eternal life (Lk 18:18; Mk 10:17). He speaks of inheritance in a

parable (Lk 20:19), and finally, promises eternal life to those who follow him

(Mt 19:29).

Early Christians realized that they shared in the inheritance

that was given to them by their merciful Father. Christian inheritance,

however, differed greatly from the territorial concept of inheritance that the

Israelite would have had in mind. The inheritances differed in four ways.

First, the Christian focus of hope is no longer the reacquisition of land

(Israel) and the restoration of its political autonomy. Second, Christians and

Christianity are not defined by borders, language or citizenship; rather it is

a worldwide, universal or catholic movement. Third, Christendom supersedes or

replaces the holy land. Finally, Christian inheritance cannot perish, be

defiled or fade because – as verse 4 states, it will be “kept in the

heavens for you.” That said, who would you rather have hold your

inheritance – Silicon Valley Banks or your Heavenly Father?!

Before I move on to Baptism, keep in mind this. As strangers

and aliens, Christians were ineligible to own land or any property. Think of

that. If you were a Christian in the late first or early second century, you

had fewer legal rights than almost everyone else. Would that factor into your

choice of Christ over citizenship? Would it today? Would you remain Christian

if you were stripped of your right to own property or free speech, your

Medicare benefits or the right to vote? Would you rather have those or the inheritance

held by our heavenly Father in His Kingdom?

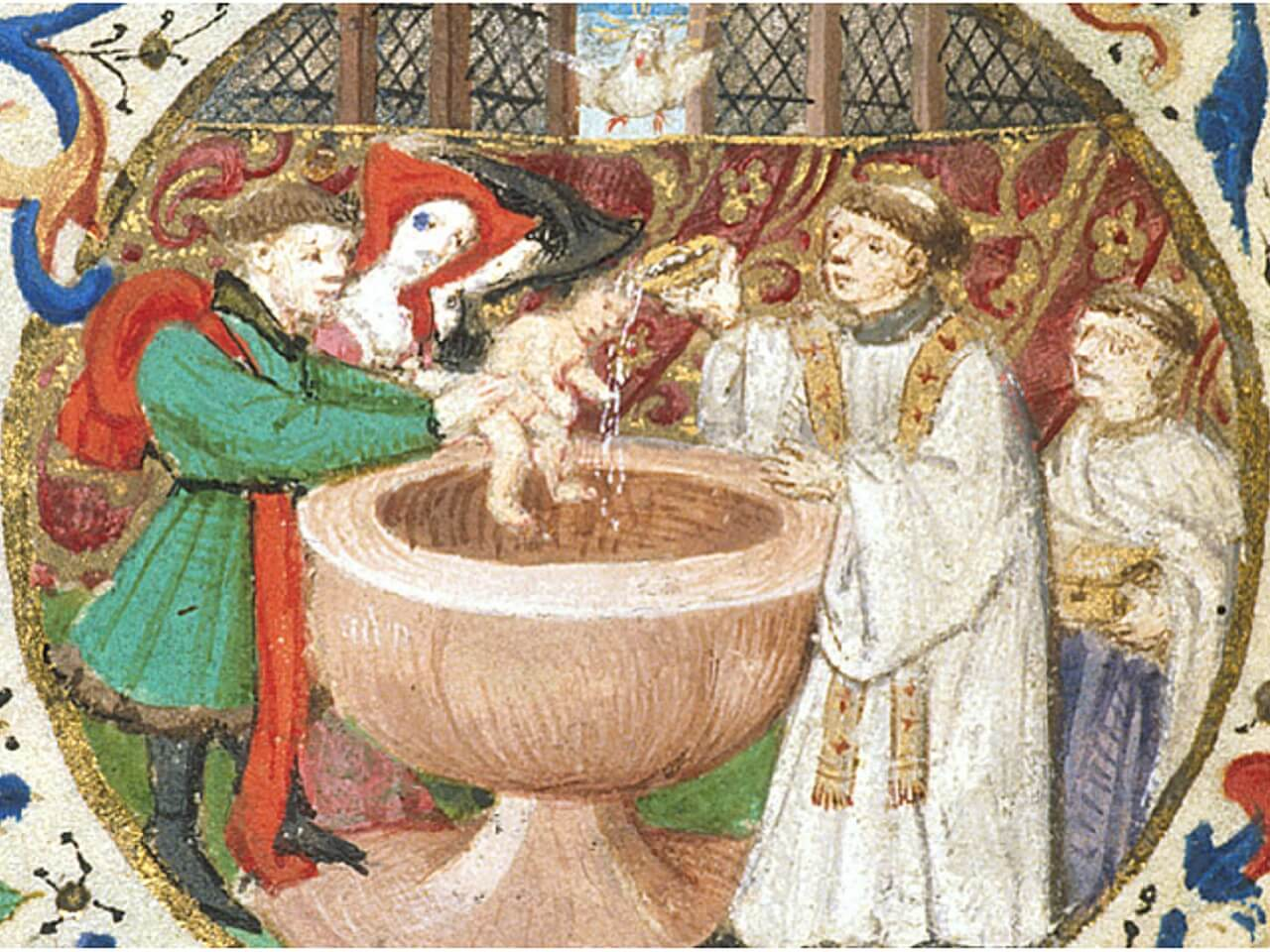

Baptism is how believers established their right to

inheritance with their Heavenly Father. By being baptized in the Name of the

Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, as the Son of God commanded his

Apostles (Mt 28:19-20), Christians became children of God.

1st Peter clearly brings out the importance of the

traditional family or the paterfamilias. The term “Father” in v. 3

expresses an intimate, familial relationship to both Jesus Christ and to the

believing members of the Christian community. Incorporation into the family of

God occurs through baptism. His baptismal theme of rebirth or new birth

permeates this section as a metaphor for the radical transformation of the

believer’s relation to God, Jesus Christ, one another and society.

While the transformation of believers’ their relationships

started with their baptism, the original source was God the merciful Father and

His word, the good news about the Lord Jesus Christ and his resurrection. Like

all newborns, these new Christians drew sustenance from the milk of the word.

But they were adults who accepted and adopted pagan ways. So, they needed to

break from their former way of life and its ungodly desires, loyalties and

behavior. These “elect” were holy children of God, redeemed by the holy Christ,

and children whose hope and trust are in God. For the modern Christian, this

begs the question of how you see your baptism as a new beginning and a break

from your former life. It should cause us to ponder at what point in our lives

our merciful Father profoundly changed us.

I was baptized 66 years ago, on April 14th. Like

one or two of you, I also accepted and adopted many of the ways of our society,

and at one point chose to divorce myself of some of its ungodly desires,

loyalties and behaviors. Yet, even today, I struggle with separating myself

with all that our society offers. There is a lot that our world today offers

that I want to embrace, and I have to reflect upon what to embrace and reject.

What helps me is the advice Martin Luther offered when he encouraged

Christians to pray daily on four points: The Apostles’ Creed, the Ten

Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Sacraments (Baptism and Holy

Communion). Reflecting on Baptism needs to be done while standing under the

Cross with Christ hanging there dying or dead. Given that we just observed Lent

and Good Friday followed by Easter Sunday enhances our reflection.

Through the Paschal Mystery – the suffering, death, burial

and resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead – I am reminded of what my Baptism

means for living my daily life and making daily choices. Peter reminded early

Christians and us today that Christ’s resurrection demonstrates God’s

life-giving and saving power, and is the basis for hope and trust in Him

despite all adversity.

Peter’s Letter reminds people of their living hope through

the resurrection of Jesus Christ because they are living in a world that offers

an attractive life. We live in a world that offers an attractive life,

according to standards different from what we believe, which is why we need

reminders like the Letter of Peter, the sound advice of Martin Luther, and the

mark of Baptism.

When we were baptized, the pastor placed an indelible mark

upon your forehead and heart – the sign of Christ’s Cross. Through baptism, we

receive the supernatural life or grace; and that mark on our forehead and heart,

as well as our soul is a permanent and distinctive quality. That is why we call

it the mark of Baptism. So, like Peter, I encourage you to think about and pray

about your baptism every day. Now, let’s move on to suffering.

We all understand suffering. It comes to us from two Latin

words: sub, which means up or under, and ferre, meaning to carry

or bear. Joined together, we have our English word, suffer.

What kind of suffering did the early Christians endure that

Peter told them that for a “little while you may have to suffer various

trials”? First, their suffering was not due to a

catastrophe, sickness, or even random acts of violence, such as floods, earthquakes,

tornados, cancer, AIDs, heart disease, a car accident or a stray bullet. His

original readers suffered affliction for the faith from hostile outsiders.

Let’s face it, in the pagan world, Christians were not welcome. They did not

worship the gods or the emperor as divine. They did not participate in socially

acceptable behavior such as debauchery or lewd conduct. They worshipped as Lord

and Savior a man convicted by the empire.

On the other hand,

not every Roman citizen persecuted Christians. Peter reminded the faithful that

suffering is potentially part of following Christ. You may have

to suffer, but it is not totally necessary that you will. God does not call you

to suffer. God calls you to obey.

Second, suffering

is not permanent. Suffering is “for a little while.” Finally, Peter

reassured his readers that their suffering is a test to demonstrate that their

faith is genuine. Such faith is more precious than gold.

Now that we have

observed Lent and entered into Easter, let’s look at the other side of the

suffering coin. Let’s look at happiness. Are you happy? Your presence here more

than likely means that you are happier than the average American. I base my

statement on an article I read recently. It was an interview with a Jesuit

Father Robert Spitzer.[1] He has spent his life

studying human happiness. The interview was conducted after the annual World

Happiness Report was issued. Life evaluations from the Gallup World Poll

provide the basis for the annual happiness rankings. They are based on answers

to the main life evaluation question.[2]

There are

different levels to happiness. I am happy when I am eating my favorite foods:

my wife’s turkey stuffing or homemade pierogies, deep dish pizza or filet

mignon. I am instantly gratified by this and other such experiences like

driving a nice car or when Maggie wants to cuddle in the morning, every

morning.

As normal human

beings, we seek happiness through fame and achievement. Often, people settle

for this level of happiness, opting to pursue careers, money and fame that they

believe will make them appear better than their peers.

Thirdly,

contributive happiness occurs when I make a positive difference in the lives of

other people. I do this because I love other people and want to make them

happy: children, grandchildren, parents, coaches, teammates, neighbors and so

on. When I visit people unable to come worship with us, I experience that level

of happiness.

Everyone can

achieve these levels of happiness regardless of their religious beliefs or

unbelief. Yet, as Spitzer says, “The fourth, and final, level of happiness can

only be achieved through connecting with that which is ultimate good, ultimate

truth, ultimate beauty and ultimate being itself: Jesus Christ. The previous

three levels fail to fulfill the deepest longings of the human heart.” Spitzer

recognizes that only through fostering an intimate relationship with God

through the gift of faith can you come to achieve this fourth level of

happiness, which is joy.

We are joyful and

happier than others not because we are better than they, but because we seek

first the Kingdom of God and the Prince of Peace. Today, the Risen Jesus Christ

gives you that gift of joyful peace through the Holy Spirit and the means of

grace – Scripture, Sacraments and Church. Even if you are suffering persecution

from others because of your faith, you can find joy in Jesus, as did the

Apostles and early Christians. As we return here one last time next Sunday,

hold fast to the peace of God that surpasses all understanding, and may it keep

your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus. Amen.

[1] https://www.ncregister.com/features/father-spitzer-happiness-begins-by-looking-for-the-good-news

[2] https://worldhappiness.report/